Somaliland Central

What you need to know about Somaliland's SovereigntySOMALILAND LIVESTOCK

Somaliland Livestock

Somaliland has a total area of 137,600 square kilometres with a coastline that extends about 850 km along the southern shores of the Gulf of Aden. It has a total population of about 3.9 million with a growth rate of 3.1% per year. But, latest data 2019 describe It is estimated that approximately 11% of the population lives in rural areas, 34% is nomadic, 2% is internally displaced persons (IDPs) and the remainder (53%) reside in major towns (MoNP&D 2017)

Agriculture is the most important sector of Somaliland’s economy. In 2012, the sector contributed more than 40% of Somaliland’s GDP with the livestock sub-sector contributing 29.5%. Livestock production in the country is mainly extensive in pastoral systems that rely on fragile natural resources. Urbanisation is estimated to increase at a rate of 15% per year. The climate of Somaliland is arid or semi-arid with daily average temperatures ranging between 20-35 °C. Rainfall varies from less than 100 mm on the coast to 700 mm inland, except in few areas where it may reach above 900 mm. The region experiences four distinct seasons: Two rainy seasons, a long one in April to June, and a short one in September to November. There are also two dry seasons, a short one from July to August and a long dry cold season from December to March. Livestock production is the primary economic activity that contributes about 60% of the area’s GDP. Livestock activities act as a source of employment, income and foreign exchange. About 60% of the population relies mainly on the products and by-products of livestock. Livestock population is currently estimated at 15 million goats, 10 million sheep, 8 million camels, 4 million cattle, and 700,000 chickens.

The economy is trade oriented with livestock exports playing a major role. Exports of livestock to the Gulf States especially to Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Bahrain, Oman, and Egypt represent the biggest share of the region’s foreign exchange earnings. An important characteristic of livestock marketing in Somaliland is the strong links between pastoralists and their urban familial counterparts. The linkages between urban population and the pastoralists, combined with culture of trading and redistribution of wealth means that virtually every one depends on livestock. In the year 1997, Somaliland exported over 2.8 million head with an estimated value of USD$ 84.4 million. Livestock exports are a major determinant of exchange rate, inflation and trade.

Livestock Production and its Limitations

Livestock in Somaliland is kept under pastoralist (Central and Eastern regions) or agro-pastoralist production systems (in the western region). Camels, cattle, sheep and goats are the main livestock produced in Somaliland. Livestock production depends greatly on the productivity of rangelands and availability of pasture and water. The arid and semi-arid climate of Somaliland can support rangeland pasture grasses, shrubs and acacia trees used by livestock. However, the productivity of these rangelands is affected by environmental degradation due to soil erosion, overgrazing, deforestation and charcoal burning. In addition, the region frequently suffers from periodic and prolonged droughts that usually lead to death of livestock due to lack of water and feed. Livestock productivity is also affected by occurrence of livestock pests and diseases, as there is no animal health extension service to help farmers deal with animal diseases. Conclusion: Somaliland Government have last 5 years created many wells for population & livestock all over Somaliland incl. increased 10 folds the health service of livestock regionals.

Livestock Marketing

Somaliland has well organized livestock trading and marketing activities. Before shipment, disease free animals remain in the quarantine station for varied periods depending on the requirements of the country of destination. For example, animals destined for Kuwait stay for 7 days, 30 days for those heading for Saudi Arabia. Before animals leave the quarantine facility, port veterinary officers certifies the health of export animals and provide exporters with a health certificate attesting that the animals are healthy and free from any disease. Livestock exporters then present the health certificate to the Chamber of Commerce who in turn issues a certificate of origin on behalf of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Livestock that are declared fit are then exported to various destinations mostly the Gulf States, which include Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar.

Opportunities to improve competitiveness of livestock production and marketing

- Enhancement of productivity of grazing areas through soil conservation, re-afforestation and better grazing management.

- Promotion of production and storage of fodder in agro-pastoral areas and develop water resources through promotion of surface and ground water harvesting.

- Promotion of private investment in input supplies (production and distribution of animal feeds, pharmaceuticals, acaricides, etc).

- Take advantage of the willingness and support of International Development Agencies and local NGOs that have initiatives to improve the livestock industry.

- Training and employment of more veterinarians, animal health and production specialists and meat inspectors with appropriate remuneration and incentives by expanding training opportunities.

- Improvement of livestock extension service through increased budgetary allocation to the Ministry of Livestock, Environment and Rural Development.

- Development of appropriate infrastructure to support the livestock sector (e.g., laboratory equipment’s for disease diagnosis, vehicles, vaccine production, upgrading of livestock markets, and construction of appropriate slaughterhouses, and acquisition of appropriate meat carriers and vehicles).

- Establishment of quarantine stations at production areas especially at Burao, Borama and Hargeisa to screen animals to ensure that only disease free animals are transported to Berbera for export.

- Establish an effective livestock market information system to furnish producers and traders with the prevailing livestock market prices in real time.

- Opening up the country to more livestock export markets through compliance with OIE animal health certification requirements.

Opportunities to Improve the Hides and Skin Subsector

- Training of butchers and flayers on proper slaughter and flaying techniques and use of appropriate flaying knives to enhance quality of hides and skin.

- Training of pastoralists/farmers, hides and skin collectors and traders on proper handling, curing, drying and preservation of hides and skins.

- Establishment of tanneries and training to improve skills in leather tanning and manufacture of leather goods.

- Assisting local enterprises to establish tanneries to produce finished leather.

- Enactment of appropriate policies to promote local processing of hides and skin and production of finished leather. Such policies should include: zero rating tax of tannery equipment and increasing tax on hides and skin exports.

The dynamics of natural resources in Somaliland: Implications for livestock production.

Description of the Somaliland climate and natural resource base: Somaliland’s environment consists of a variety of ecosystems, comparatively limited biodiversity and scarce water resources (Figure 1) (Monaci et al. 2007). The topography is characterized by three main landforms: (i) Piedmonts and the coastal plain (Guban) situated southward from the Red Sea with elevations ranging from seas level to 600 m; (ii) Hills and dissected mountains (Oogo) of rugged features and rising to more than 1,500 m; and, (iii) the plateau (Hawd) with large areas of undulating plains. There are three main climate zones in Somaliland: (i) desert; (ii) arid; and, (iii) semiarid.

The vegetation is characterized mostly by grass, shrubs and woodland. Perennial grasses such as Lasiurus scindicus and Panicum turgidum and scattered trees such as Balanites orbicularis, Acacia tortilis and Boscia minimiflora are the most predominant vegetation in the coastal zone of Somaliland, particularly in the western part. Juniperusprocera woodland is more present in the mountainous areas. In the plateaus, Acacia etbaica bushes and woodland as well as open grasslands or bans are common. In these areas pressure on grazing is intense. The Hawd is characterized by Commiphora woodland and bushes. The Nugaal valley largely supports sparse trees such as Acacia tortilis and shrubs (MoNP&D 2017).

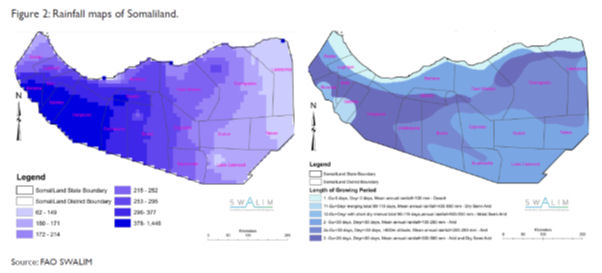

Temperatures are generally high throughout the year, with the maximum being 36–38°C in the coastal areas (Basnyat 2007). Rainfall has bimodal distribution, with the first main rainy season, Gu, occurring between April and June and the second, Deyr, from August to November. The two dry seasons are Jilaal (December and March) and Hagaa (July and August). It is important to note that areas around Sheikh, Hargeisa, Borama and Erigavo towns receive the higher volumes of rainfall, an average of 400 mm per year, supporting limited crop production. The northern coastline is characterized by low rainfall amounting to less than 100 mm per year. The rest of Somaliland receives an annual rainfall ranging from 200 mm to 300 mm (Figure 2) (Paron and Vargas 2007).

The low precipitation amounts have led to scarce water resources, and absence of permanent rivers and lakes. Groundwater (from dug wells, boreholes and springs) is the main source of water for the majority of the people. This water source is harnessed by the rural and urban population to meet domestic and livestock water needs as well as for small-scale irrigation. In 2012, according to FAO SWALIM (Petersen and Gadain 2012), there were a total of 1,037 water sources of which more than half were shallow wells. Dams were restricted only to the region west and south of Hargeisa, while springs were found in the mountainous regions, particularly in Awdal, between Hargeisa and Berbera and around Erigavo regional towns

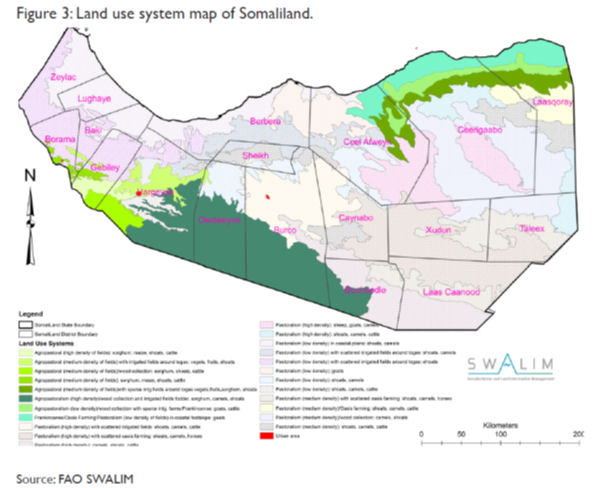

The major land use is pastoralism with agro-pastoralist zones in the southwest where most rain-fed cropland is found and the northeast where irrigated cropland is found. Cattle are mostly found in the west, the wetter part of Somaliland, camels in the driest and goat and sheep elsewhere.

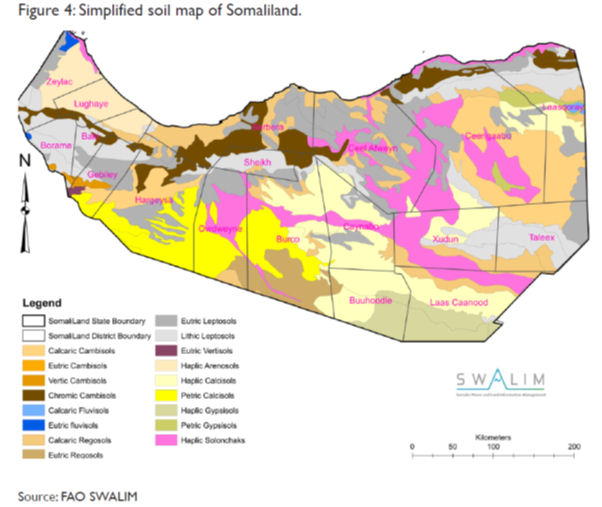

Somaliland has different types of soils (see Figure 4 for a simplified soil map). The soils are Leptosol, Cambisol, Regosols and Solonchaks2. Overall, the soils have poor structure with high permeability, low moisture retention capability and inadequate internal drainage. Though the nature of these dryland soils makes them of poor quality, the clearing of vegetation for farming purposes, cutting trees for charcoal production and overgrazing have magnified their deficiencies.

The progressive decline in soil quality (fertility) has impacted on the productivity of both farming and grazing lands.

Historical review of land use

A review of the history of land use and land-use planning in Somaliland reveals five different phases: the pre-colonial time (before 1887), the colonial time (1887–1960), civilian rule of government after independence (1960–1969), revolutionary military socialist regime (1969–1990) and the collapse of the revolutionary regime (after 1990). Each of these periods have had different policies and land-use planning processes or influences resulting in different land and resource utilization approaches (Venema et al. 2009).

In the pre-colonial time a set of customary norms (known as Xeer) provided the rules of interaction among members of a clan and other neighbouring groups. They guided access to and use of pasture, water and other natural resources, and every member of a clan had the right of access to the rangelands and water resources within the territory inhabited by the clan. Whereas the rangelands themselves were managed communally, private property rights were assumed for any infrastructure built on the rangelands. This property fell under Islamic law and could be inherited under those conditions. In wetter areas and enclosures for cropping, every household within the community was designated a plot for cultivation. Land in urban areas was considered privately owned. To a certain extent, this customary law is still applied today (Venema et al. 2009).

During the British colonial rule, much common land including in the pastoral areas was privatized, individualized and then registered, with title deeds issued for agricultural land covering a 50-year lease period. Other land uses were defined vis-à-vis grazing reserve— which aimed at increasing the availability of fodder in the dry period; forest reserve; and public water points. This rule favoured settlement of pastoralists (Venema et al. 2009).

The climate hazards have also contributed to increased soil degradation and erosion, progressive reduction in rainfall and higher temperatures that have not only intensified the negative impacts on natural resources but also caused additional changes that include altering the livestock mating calendar (Hartmann and Sugulle 2009).

It is estimated that about 30% of Somaliland’s land is severely degraded (MoNP&D 2017). The most common types of degradation include loss of vegetation cover, soil erosion3 and deforestation4. The vegetation types that have been highly exposed to land degradation include grass, forbs, sparse shrubs, and short trees, which are the prime sources of feed for livestock. The loss of these vegetation types has been attributed to livestock grazing and unregulated agricultural activities in the rangelands. The increase in agricultural activities has been associated with increasing land enclosures, all of which have affected the traditional livestock grazing patterns in some areas and led to the concentration of livestock in others. Besides, the proliferation of Berkheds (traditional underground water reservoirs) has also increased livestock and population concentration in certain areas where the surrounding vegetation has been exposed to further deterioration. Furthermore, the loss of native vegetation, has been accompanied by proliferation of invasive plant species such as Parthenium weeds (Keligii noole), Prosopis (Garanwaa) and Cactus (Tiintiin) all which have high seed production capacity and adapt easily to a wide range of climatic and soil conditions. Though livestock will for example eat Prosopis pods, they are generally unconsidered unsuitable for livestock particularly in their raw state and the loss of grazing land to these invasive species outweighs any benefit (Omuto et al. 2009; Vargas et al. 2009).

These changes have contributed to the increase in conflicts over land use. Understanding the dynamics that drive land use change is important for supporting policymakers’ development of a land use policy that contributes to the reduction of land conflicts. Such policies can support the emergence of a multifunctional landscape5 that accommodates the pastoral production system that needs to adapt to new climatic conditions as well as the new emerging claims from settlers (Leemans and de Groot 2003). The objective of this study was to investigate and document the current natural resources relevant to livestock production in Somaliland, identify the major drivers of land use change at landscape scale that influence landscape functions, and identify pastoralists’ existing strategies to adapt to these changes. It is envisaged that the information generated will inform policy formulation that will accommodate these new and evolving land uses by combining, where possible, different landscape functions.

Livelihood sources

Livestock and crop production are the principal sources of livelihood for the agropastoral communities in the M&G regions. Approximately 88% of households own some type of livestock. Livestock numbers owned per household are reported in Table 5. The mean numbers of small stock owned per household are 15, and 16 sheep and goats, respectively. Mean ownership of cattle and camels are 3 and 1.5 per household, respectively. Additionally, each household, on average keeps one donkey and 4 chickens.

Vegetables were ranked as the most important source of livelihood by 47% of household respondents, while 44% ranked grain crops (sorghum, maize, cowpea) as the most important (Fig. 2). Only 26% of respondents ranked livestock as the most important source of livelihood, in contrast to the focus group discussions where livestock were given the first rank by four of the seven villages targeted for focus group discussions (Table 6). Labor wages were most important source of income for only 19% of households. Grain crops and livestock were ranked as the second most important sources of livelihood by 44% and 41% of households, respectively. A majority of households reported wages as the third source of their livelihoods. Less than 7% of households ranked livestock, grain crops, and vegetables as the third sources of income

Mining and mineral resources

Somaliland is rich in mineral resources. It has one of the largest gypsum deposits in the world. There are also deposits of coal, quartz, iron, gold, gems, heavy minerals and oil. There is huge potential for the development of the mining sector which if realized could catapult Somaliland into middle income country in a relatively short period. The key to the development of the sector is the formulation of appropriate policies and mining codes that meet international standards and are attractive to foreign mining companies.

Somaliland also has a range of known mineral resources such as coal, gypsum, and limestone, various gemstones as well as precious and base metals such as gold, copper, lead and zinc that should be further investigated since they present prospects for income and employment generation. Oil exploitation is also believed to be a realistic possibility based on oil finds in Yemen in similar geological formations. What is needed is a competent and transparent public regulatory and contracting authority within government to manage the decisions over rights by the private sector to exploit these resources, and a general strategy that can ensure appropriate and sound use of public resources. Given the environmental conditions with much sun and wind, renewable energy sources should also be explored. At the same time, a strategy for improving the regulatory and policy framework is needed, which would have to include capacity-building elements to maintain the existing network, as well as looking at the cost benefit of importing energy from neighbouring countries and means to decrease wastage.

Exports and Imports

Somaliland economy is a pastoral economy. Livestock contributes to over 65% of the GDP. Hence livestock constitutes the principal export from Somaliland. The main destination of Somaliland’s livestock exports is Saudi Arabia. Yemen is the second most important market.

Key economic activities. The traditional livestock and agriculture sectors dominate the economy of Somaliland and hence the employment of its people, since much of it is labor intensive. Livestock rearing, trading and exporting represent the dominant productive activity in Somaliland, followed by crops, fisheries, and forestry.

Crop production is sizeable in rainfed and irrigated crop production in Somaliland, cultivating about one-third of the area suitable for agricultural production. Rainfed crops include sorghum, maize, cowpeas, groundnut and sesame. Irrigated crops are citrus, papaya, guava, water melons and vegetables such tomato, onion, cabbage, carrot, and peppers. The sector has been vulnerable to droughts and increasingly constrained by the huge damage done to the environment and the lack of available land for cultivation. Crop production: Given Somaliland’s geographic features, it seems likely to remain a net food importer, financed by exports of livestock and fish products. The cost of producing food is relatively high, but the agriculture sector will remain important given the rather labour intensive production methods and importance for local food supply.

A strong private sector has emerged in Hargeisa and other urban centres as a result of the prolonged peace and achievement of relative security, and is currently involved in a wide range of economic activities and import-export businesses. Investments by the private sector in all these cities has resulted in the delivery of goods and services such as electricity, telecommunications, domestic water supplies, and urban waste disposal.

Other productive sectors. Looking beyond traditional livestock and agriculture, there is potential to diversify the economy in rural areas, and provide opportunities for off-farm income-earning opportunities. Currently, most of the population is involved in subsistence based production, which is highly labour intensive.

Agriculture, livestock and fisheries

The agricultural sector, including livestock, is top priority since the majority of the population derive their livelihoods from it. The key position of agriculture in the economy means that there remains a strong imperative to develop the sector to ensure food security, employment, income generation, and increased export of agricultural produce. Agriculture has the potential to spur growth, reduce poverty, and enhance food security. The development of agriculture is vital for meeting the Millennium Development Goals.

Food Security

Ensure the availability and the affordability of stable food commodities particularly for the poor by pursuing policies that encourage production and higher productivity of stable foods such as sorghum, maize and beans.

Media institutions are moving towards a free, market-oriented system, but are still constrained by weak information delivery capacity, lack of professional skills on behalf of journalists, and close links to political factions. Radio stations are the main tool for delivering information and raising public awareness in Somaliland. However, coverage in rural and remote areas, where information is needed most, is limited. Improved coverage is thus a key priority that could be accomplished through establishing low cost community radio stations or alternatively repeating stations in rural areas. In addition, capacity building of media professionals will be important, as well as the development of a communications and information policy framework that can guide the sector’s involvement, including in civil and social education efforts. The participation of women in the media sector, including at management levels, is crucial to address gender needs and priorities. In order to preserve the freedom of press, it is necessary that a general code of conduct be adopted for the media and adequate space created for private media, especially the radio.